The History of British Punk

Punk was meant to sweep away the bloated dinosaur of progressive rock and the blandness of pop music. In that it succeeded, changing the course of popular music completely. At the time it was outrageous, even scandalous, and the newspapers played up the idea of safety pins through cheeks and swearing on television. But from a small beginning, when punks feared violence from others, it grew to become a huge global musical movement.

The Beginnings

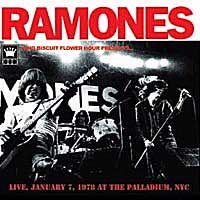

It’s been argued that punk existed in New York before it hit London, with groups like the Ramones and Patti Smith playing venues like CBGB’s in the Bowery. In London, though, it was far more political, a cry against the established system of government, from groups like The Sex Pistols and the Clash.The Pistols arose from a clothes shop run by Malcolm McClaren and Vivienne Westwood, where the members of the group met and rehearsed under McClaren’s direction. However, once they began playing shows early in 1976, apart from a small coterie of fans, they found people not so eager for their music.

McClaren was a consummate entrepreneur, though, and word about the Pistols spread quickly, along with rumours about their outrageous behaviour, which was confirmed when they swore on national television. But, following the theory that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, the record companies came calling. The Pistols signed with EMI before being dropped for their behaviour, then A&M, with the same result – making themselves quite rich along the way. A deal finally stuck when they signed to Virgin Records and began releasing records, one of which, God Save the Queen, was banned from radio but still topped the charts.

Their only real album, Never Mind the Bollocks, sold very well, one of punk’s seminal works. But they split up in 1978 as they finished a U.S. tour. Their influence, though, spread wide, as so many young bands took them as an inspiration, even though singer Johnny Rotten (John Lydon) never seemed to take the ethos of punk too seriously.

The Clash

The leader of The Clash, Joe Strummer, had played in a pub-rock band, making rough, raw rock’n’roll. Teaming up with three aspiring musicians he formed the band, which was deliberately political from the outset. They began releasing albums in 1977 to great critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic, which increased with their other discs. London Calling, their third album in 1979, made many best of the century lists. But by that time, although they’d retained their punk roots, they’d developed into a powerhouse rock band, and hit true pay dirt in 1982 with Combat Rock, which made them global stars, although by then they were on their last legs, imploding a year later.The Damned

In terms of record releases, both The Sex Pistols and The Clash were eclipsed by The Damned, who issued the first punk single (New Rose) and album (DamnedDamnedDamned). How truly punk they were was a debated issue at the time. But in the early days there were so few punk bands that even their pop sensibilities welded onto punk music were accepted and embraced. Curiously, perhaps, they outlasted all their contemporaries.The Venues

Punk found a short-lived home at a London club called the Roxy at the beginning of 1977, after the 100 Club had hosted a two night punk festival in autumn 1976. It gave opportunities to many of the young punk bands, which could be extremely young (Eater, for instance, had a 14-year-old drummer), and inexperienced (one of the deliberately liberating things about punk was that instrumental ability wasn’t necessary to make music and join a band).The first punk tour, with The Sex Pistols and The Clash headlining, found itself the victim of punk’s publicity, as councils around the country cancelled date after date – less than a handful were played in the end.

Did Punk Die?

The idea of punk, of kids getting together regardless of ability, just to make music and release their frustrations, has never really died. That’s probably punk’s biggest legacy, and one which has lasted, just as the great albums have remained influential. Groups like the Slits showed that women could be punk musicians as much as males, and make music that was even more challenging. Nor did the fashions of punk – spiky hair, jewellery, loud clothes – vanish; you can still see teenagers dressed that way.Although punk influenced things musically, and still does, the actual fad of it had passed by the end of 1979. There was only so far it could go, and by then it had exhausted itself. It was a limited form, but its energy and anger was vital, an infusion of new blood when music was in the doldrums. It picked up on the rawness that had fuelled the best 1960s pop-rock and stripped it down to the bone. It gave music what it needed at the time, and helped propel it through the next few years.

- Space Rock

- Jazz-Rock Through The Ages

- All About Folk Rock and It's Success in the 1970s

- British Reggae

- New Wave Music in The 70s

- Pop Idols of British Pop

- Post-Punk Music

- The Emergence of DIY Record Labels

- Two Tone Music Craze

- Singer-Songwriters

- The Rise & Rise of Elton John

- 1970s Guitar Heroes

- Hard Rock and Heavy Metal

- Old Grey Whistle Test

- A Biography of The Bay City Rollers

- The Impact of Festivals on The Music Industry

- Virgin Records - Richard Branson and Nik Powell

- All About Progressive Rock

- T Rex- The Rock Band

- The History of Glam Rock

Re: Bands in Hamburg

hitchhikers 65 they played there

Re: Lonnie Donegan

Lonnie is at once over-rated (he had a bit of a history of self-serving, e,g, adding his name to Woodie Guthrie's on composer credits), and…

Re: Bands in Hamburg

is there a list of bands that played during the sixties anywhere. I am looking for bobby Bobby and the blue diamonds

Re: Skiffle, Music of the Fifties

Hi , I am a bit of an avid car booter , collect and deal with all manner of interesting items online and have recently come…

Re: All About Gig Package Tours

I'm researching information about my late father-in-law, who used to play guitar in england, he often 'backed' or 'filled-in' for…

Re: The History of Britpop

I love this site however i thing it could do with some sort of Britpop facts in bullets points or whatever.

Re: Cliff Richard

Cliff's career has out lived many singers and bands over the past 55 years, Well done cliff

Re: T Rex- The Rock Band

"Shady politician in my bed Tying bolts of lightning to his head...." Who else but Marc could pull this style off! Marc and T-Rex's…

Re: Virgin Records - Richard Branson and Nik Powell

These days, of course, Virgin, both shops and label, are just a memory, but for those who bought music in…

Re: The Impact of Festivals on The Music Industry

Festivals are big business these days, and even if they don’t all make money, or some take a year off (like…